There are few higher tributes that can be paid to a footballer than to be voted their team’s best player in a finals series.

That says you stand up when it matters most - when the battle is at its fiercest and the stakes are highest. There is no better measure of a player’s ability to play well in big games.

At Collingwood, the trophy for Best Player in a Finals Series is named after one of our greatest figures, Bob Rose. The award itself was first presented as early as 1926, and Rose’s name was added to it in 1988. It has been won by many of the club’s biggest names, including Syd Coventry, the Collier brothers, Len Thompson, Des Tuddenham, Nathan Buckley, Gavin Brown, Peter Daicos, Scott Pendlebury and Dane Swan.

With the Pies back in September action again, it seems like the perfect time to pay tribute to some of those who have won this award over the years.

To see more on the Bob Rose Award, including a full list of winners, check out the page on Collingwood Forever.

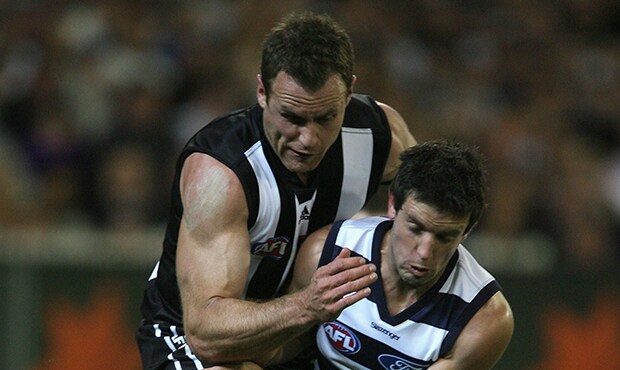

Collingwood supporters have many vivid memories of James Clement, one of the great defenders of the modern era. He was cool, calm, authoritative, composed, long-kicking, a leader.

He was all of that, of course. But one of his other great qualities is often underrated – his ability to stand up in the biggest of games

"He's been sensational for us," Licca said at the end of the year. "He's always been a very good player and now more people are starting to realise it, but I think people within the club who know their footy always knew he was a very good player."

By the time Clement won his second best finals player award, in 2006, the whole football world knew how good he was. By then he'd also added two Copeland Trophies to his stellar footballing CV, confirming his status as one of the Magpies' greatest ever pieces of recruiting

Clement’s consistency and his rare ability to win his contests, regardless of the result, saw him become a star in a revamped team that would contest the 2002 and 2003 Grand Finals. He was third in the Copeland Trophy in his second season at the club, then won consecutive best-and-fairest awards in 2004 and 2005, and finished second in 2006. He was named in two All-Australian teams (2004-05

"He was probably the best defender in the competition for two or three years," Scott Burns maintained. "He was an All-Australian lock. I still can't believe he didn't make it (the team) in a few other years."

Clement took on and eclipsed some of the best forwards of his time, and is widely remembered for one clash in 2006 where he outpointed Essendon's James Hird so comprehensively that the AFL subsequently introduced the “hands in the back” rule

"Jimmy could play on the smallest of forwards and the tallest of forwards, and he would knock them all over," Nathan Buckley said. "He was hard, really hard, and he made himself that on and off the field.”

He was rarely beaten one-on-one, was an exceptional rebounding defender and in an age where metres gained was not necessarily a focus, his ability to break free from his opponent and roost the ball 60m out of the zone was crucial to the Magpie game plan.

As understated as he was off the field, Clement proved extraordinary guidance and inspiration on

James Clement was always a consistent finals performer for the Pies, right up until his final match in 2007.

He may well have captained the club had he not retired at the end of 2007. Fittingly, he was among Collingwood's best players in the heartbreaking preliminary final loss to Geelong that year. Few took much notice when he gave a wave to the crowd as he left the MCG that night. He was

Collingwood's quiet-achieving rock in defence

Collingwood supporters have many vivid memories of James Clement, one of the great defenders of the modern era.